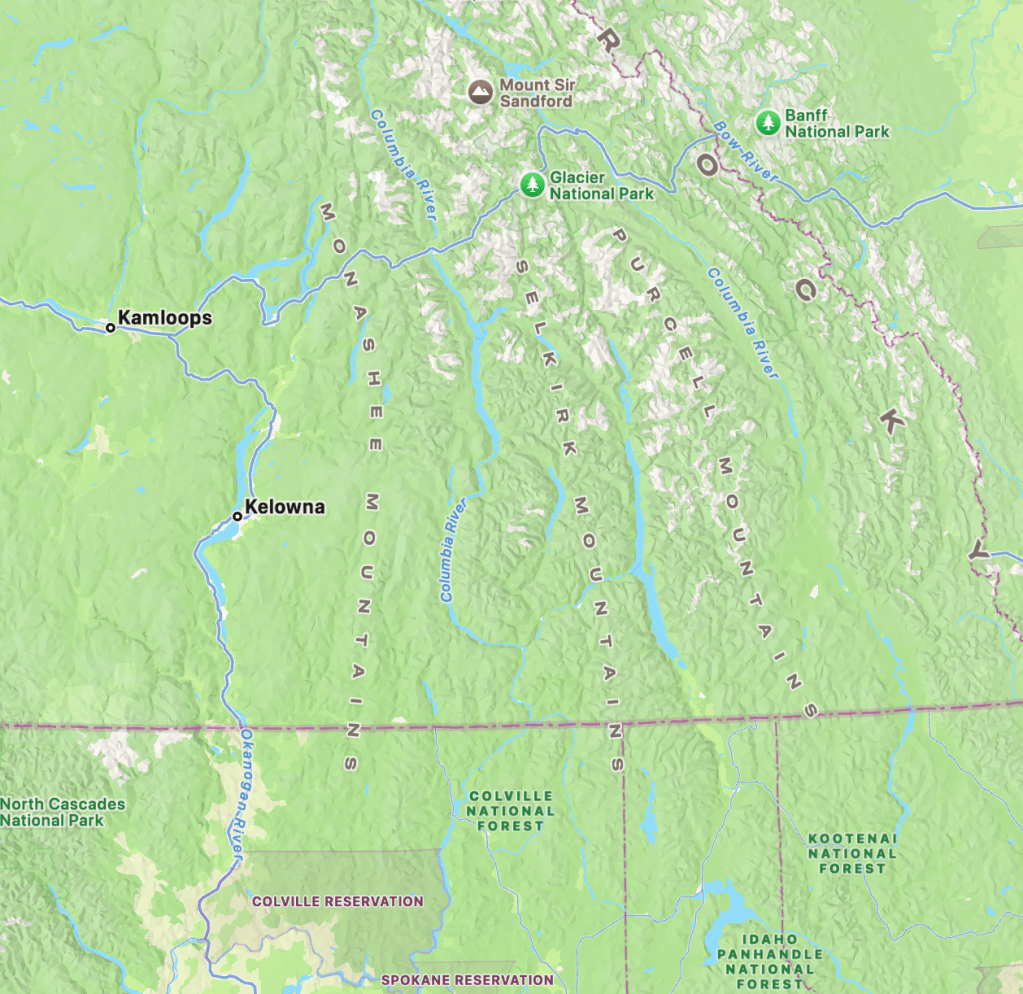

With a protected corridor across the Columbia Highlands, wildlife species will be able to travel east to the Rocky Mountains or west to the Cascade Range in search of favorable habitat, new territory, and potential mates. Much of this Cascades to Rockies connection in the U.S. and Canada is preserved in national forests and tribal lands, as well as state, province, and local preserves. Consequently, this landscape serves as the primary east-west migration route for wildlife between the two great north-south mountain systems in the North American West.

The collision of tectonic plates pushed up the mountain ranges millions of years ago. Following the buildup, the land stretched, causing pieces of the lithosphere to rupture and collapse relative to the mountains on either side. These “normal faults” resulted in a separation of the Rocky Mountains on the east with the Columbia Mountains on the west, which are thought to be somewhat older than the Rockies given that mountain building occurred southwest to northeast.

Four major subranges make up the Columbia Mountains Natural Region: the Cariboos at the northern extent in British Columbia plus the Purcells, Selkirks, and Monashees that run parallel from BC across the international boundary into the U.S. These ranges lie north-south, at right angles to the mountain-building force pushing from the west that rumpled the land surface.

In the U.S., the Purcells range on the border of Montana with the Idaho Panhandle, while the Selkirks occupy the Panhandle’s northwest border and the adjacent corner of the state of Washington. The Monashees lie west of the Selkirks in northeast Washington.

The Columbia Mountains are named for the Columbia River that flows north from Columbia Lake lying in the Rocky Mountain Trench in BC. Passing the northern end of the Purcells, the river later rounds to the west and south to outline the northern end of the Selkirks. The Columbia, having turned south, passes between the Selkirks on the east and the Monashees on the west. These geologically distinct foothills of the Rockies are collectively referred to as the “Columbia Highlands,” taking its name from the river and mountain range.

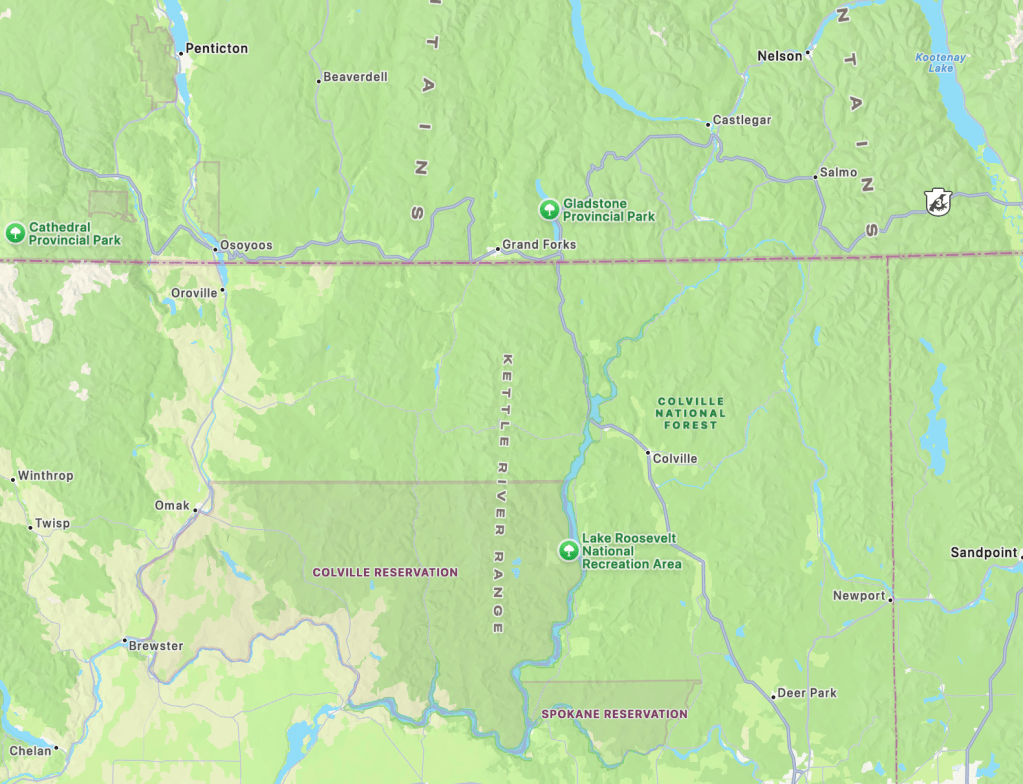

The southernmost subrange of the Monashees, where they enter the U.S. into Washington, is called the “Kettle River Range.” The Kettle River rises in the BC Monashee Mountains and flows south and southeast to dip into Washington then turn northeast back into BC where it makes a hairpin turn to the south, outlining the northern reaches of the Kettle River Range. The river then flows back into Washington where it eventually joins the Columbia River. From the Kettle River at its northern end, this mountain subrange extends south, bordered on the west by the Curlew Valley and the San Poil River and on the east by the Columbia River, ending on the south where the big river turns west.

Descending from Washington Pass in the Cascades, I drop into the valley of the Methow River. The Methow tribe, a small, detached band of Okanagan-speaking people, the sp̓aƛ̓mul̓əxʷəxʷ, lived along the river that also bears their name. Then east through a section of Okanogan National Forest and Loup Loup State Forest, the highway enters the sagebrush flats and ranchlands of the Okanogan Valley surrounded by rolling hills.

A dramatic change from sharp mountain peaks of the Cascades to more gentle landscape along the Okanogan River. Both the Methow and the Okanogan rivers reach confluence with the Columbia River to the south. East of these valleys lie the Okanogan Highlands and, beyond, the more dramatic Columbia Highland foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

The nonprofit Conservation Northwest, in addition to its efforts in the North Cascades, has worked for over twenty years to reestablish and preserve a wildlife corridor between the Cascades of the Pacific Wildway and the Rockies of the Western Wildway. This Cascades to Rockies corridor provides connectivity for the West’s iconic species—mule deer, elk, moose, bighorn sheep, mountain goat, wolverine, Canada lynx, wolf, mountain lion, black bear, and grizzly. With a protected wildlife corridor across the Highlands, these native species will be able to travel east to the Rockies or west to the Cascades in search of favorable habitat, new territory, and potential mates. A multitude of smaller creatures in the ecosystem will follow in their wake. The mountain forests and flatland sagebrush inhabiting this corridor provide the necessary shelter and resources for the survival of this assemblage.

Joining US 97, I turn north along the Okanogan River, with the Colville Reservation on the east. The Confederated Tribes that live on the reservation consist of the Lakes, Colville, Okanogan, Moses-Columbia, Wenatchi, Entiat, Chelan, Methow, Nespelem, Sanpoil, Palus, and the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce, who together originally occupied 39 million acres in eastern Washington and portions of British Columbia, Oregon, and Idaho. While the reservation to which they were confined in Washington covered several million acres, the maneuverings of the U.S. government, spurred by the discovery of gold in the northern half, managed to reduce the size to its current 1.4 million acres.

While north-south US 97 is considered a scenic byway in this less-developed region of Washington, it does pose a barrier for east-west wildlife movement between the Cascades and the Kettle River Range. Along a 13-mile stretch of US 97 south from Janis Bridge that spans the Okanogan River, around 350 mule deer are killed annually by vehicles. Conservation Northwest and the Mule Deer Foundation chapters in Washington initiated a Safe Passage 97 project to address the death toll as well as the safety of vehicles traveling the highway. As a first step, the project engaged local partners and donors to raise $260,000 for wildlife passage improvements under Janis Bridge that consisted of removing brush and grading a path on the south side under the bridge. Fencing was added along the highway to funnel wildlife to the underpass. Since then, the Washington State Department of Transportation has documented a 90% reduction in vehicle-deer collisions at that location. The overall project will include several more underpasses, associated fencing.

Wildlife traveling east to west have an easier route once they encounter the less-developed Colville Reservation and the 1.5 million-acre Colville National Forest north of the reservation. A significant portion of the forest was once part of the reservation, referred to as the “North Half.” This area hosts numerous wildlife species that may travel east to the Rockies or west to the Cascades. This connection is vital for maintaining genetic diversity across populations.

While the Colville Reservation serves as a relatively cohesive area across the Okanogan Highlands to the Kettle River Range, Colville National Forest on the north is not circumscribed by a single boundary. The separate units of the forest appear on a map as a partially completed jigsaw puzzle. A strip of the Colville separates Loomis State Forest from Okanogan National Forest in the Cascades. Then on the other side of the Okanogan River several units lie north of the reservation. Still, these national forest patches with their limited protections provide stepping-stone refuges for connectivity across the landscape.

Farther to the east lies a more intact north-south portion of Colville National Forest that encompasses the northern half of the Kettle River Range; the southern half lies within the Colville Reservation. The Kettle Range consists of a single long mountain ridge appropriately called the “Kettle Crest.” Within this national forest portion of the Kettle Range, 100,000 acres have been identified as existing or proposed roadless areas, much deserving of wilderness protection, including areas of old-growth forest. However, despite longtime efforts no wilderness has been designated in the Kettles.

At the Kettle River’s confluence with the Columbia, Kettle Falls on the larger river was once a famed salmon fishery for indigenous peoples. Salish speakers called the falls where they gathered to fish Shonitkwu, meaning “roaring” or “noisy” waters because of the sound from the fifty-foot drop of cataracts that could be heard a mile or more away. Explorer David Thompson, leading a mapping expedition from Montreal, arrived at the falls in 1811. The French-Canadian voyagers called the noisy falls, La Chaudière, which translates to “boiler” or perhaps “cauldron.” Canadian artist Paul Kane saw the falls in 1847 and recounted, “These boulders, being caught in the inequalities of rocks below the falls, are constantly driven round by the tremendous force of the current, and wear out holes as perfectly round and smooth as in the inner surface of a cast-iron kettle.” And so the name.

The kettle sound is heard no more because construction of Grand Coulee Dam created Lake Roosevelt (named for Franklin), which submerged the falls as well as Native American homes and sacred sites. The lake was designated a national recreation area in 1946. The dam, completed downstream on the Columbia River in 1941 with a labor force of 8,000, was the largest masonry structure in the world at the time.

The salmon are also gone from Kettle Falls. Since no fish ladders were included in construction of Grand Coulee Dam to enable fish to migrate upstream, the upper Columbia was cut off from the salmon runs spring through fall. The indigenous-led reintroduction of salmon in the upper Columbia is called the “Columbia River Salmon Reintroduction Initiative.” This collaboration of the Syilx Okanagan, Secwépemc, and Ktunaxa Nations with the governments of British Columbia and Canada combines indigenous knowledge with western science to accomplish the goal of “Bringing the Salmon Home.” As reported in the Initiative’s Annual Report for 2023-24, tagged salmon fry released in the upper Columbia made it downriver through all the dams. After reaching maturity at sea, several returned as adults to the lower Columbia in 2023. In a collaborative monitoring project, some adult salmon released by Colville Confederated Tribes in the upper Columbia returned to Canadian waters and exhibited spawning behavior.

The Columbia River separates the long crest of the Kettle River Range from the Selkirk Range that’s characterized by several ridgelines. While the Selkirks reach lofty heights in British Columbia, they are more muted on the south as they cross the international border. Only two peaks in the Washington Selkirks reach over 7,000 feet—Gypsy Peak (7,323 ft.) and Abercrombie Mountain (7,312 ft.). Author Rich Lander says, while commenting on Columbia Highlands by Romano, “The Columbia Highlands are special precisely because they are neither too high nor too low, but rather just right for habitation for a long list of remarkable species.”

And for the east-west migration of those species. Romano says, “A transition zone between the wet Cascades and the drier Rocky Mountains, the highlands act as a land bridge for wildlife populations from these greater ecosystems.”

Subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, Western redcedar (clockwise from upper left)

The in-between state of this east-west linkage means the Highlands host myriad animal species from both mountain ranges amid mountain forests of western redcedar and western hemlock in the valleys; Englemann spruce and subalpine fir on slopes and in cool, moist locations; in drier areas and where the land has been disturbed, including areas of fire succession, Douglas fir, western white pine, western larch), lodgepole pine, grand fir, and ponderosa pine. Deciduous trees play a secondary role in the ecosystem.

The Selkirks lie within two national forests, the easternmost unit of the Coville and the Kaniksu National Forest that straddles the border of Washington with Idaho and is managed as part of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests. While Canada’s larger portion of the Selkirks contains many protected areas, including their Glacier National Park, Mount Revelstoke National Park, and numerous provincial parks, the U.S. portion of the Selkirk Range contains the only permanently preserved area, a wilderness, in Washington’s portion of the Columbia Highlands.

Wanting to see this lone wilderness area, I head out of Metaline Falls. Following Romano’s directions in Columbia Highlands, east from Sullivan Lake following Forest Service Roads, I ascend Salmo Mountain to road’s end at the Salmo Mountain Lookout at 6,828 feet.

The 41,335-acre Salmo-Priest Wilderness tucks up against the British Columbia-Idaho corner of Washington. From there it spreads southwest, separating at Salmo Mountain to run along two long ridges of the Selkirks. The name of the wilderness comes from BC’s Salmo River and Idaho’s Priest River. “Salmo” is Latin for “salmon,” while “Priest” seems to have descended from the Kalispel “kaniksu,” meaning “black robe,” which they called the missionary priests who arrived to convert them.

From the mountain summit, I view the surrounding mountain ridges of the wilderness, north toward Canada and southwest to Gypsy Peak, the tallest mountain in eastern Washington. The old lookout stands on the summit, staffed from construction completion in 1964 until 1976 when such fire lookouts were no longer needed. The square, white, flat-roofed structure poses prominently, rising on stilts above nearby trees. Stairs rise from the ground to a promenade encircling the lookout that once offered fire watchers a 360-degree view.

The Washington Departments of Fish & Wildlife and Transportation recently issued Washington Habitat Connectivity Action Plan (2025) recognizing that, “Terrestrial habitat connectivity is critical to maintaining Washington’s biodiversity, ecosystem resilience, and climate adaptation potential. As landscapes become increasingly fragmented due to transportation infrastructure, urban expansion, and other land-use changes, wildlife populations face growing barriers to movement, increasing risks of genetic isolation, habitat loss, population extirpation, and wildlife-vehicle collisions.

“Our analysis ranked the ecological and safety status of every road mile in the state highway system, called the Full Highway System Rankings. From these rankings, we identified a Long List and a more selective Short List of transportation Priority Zones for road barrier mitigation to facilitate safe passage for wildlife and reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. These transportation priorities and the adjacent connected landscapes leading up to and away from these barriers are priority locations for connectivity conservation in Washington.”

The thirteen Connected Landscapes of Statewide Significance identified in the Action Plan include the Cascades to Rockies corridor.

Cascades to Rockies Connected Landscape of Statewide Significance

Courtesy of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

The Columbia Mountains are at the farthest extent of influence from the Pacific. As moisture moves eastward from the ocean, it waters the coastal temperate rainforest. Then passing over the Cascades and BC’s Coast Mountains, the clouds drop more moisture as both rain and snow. Still, there’s adequate moisture in the clouds when they get to the Columbia Highlands to produce enough rain and snow on the western flanks of the mountains to meet wet conditions for scattered pockets of this inland temperate rainforest that is farther from an ocean than anywhere else in the world. David Moskowitz calls this the “Caribou Rainforest” in his book, Caribou Rainforest, from Heartbreak to Hope, for this is the home of the mountain caribou, perhaps the most endangered large mammal in North America.

The old-growth forest these caribou rely on takes 80-150 years to grow enough lichen in the moist internal air of the rainforest to provide winter food for the mountain caribou. There is no replacing this forest in the foreseeable future once it is gone. Once again, indigenous groups are working to save this caribou subspecies and the old-growth forest on which they depend.

© Russ Manning. All Rights Reserved.

A pdf of much longer text and complete references for Cascades to Rockies: Columbia Highlands may be downloaded at the link below.