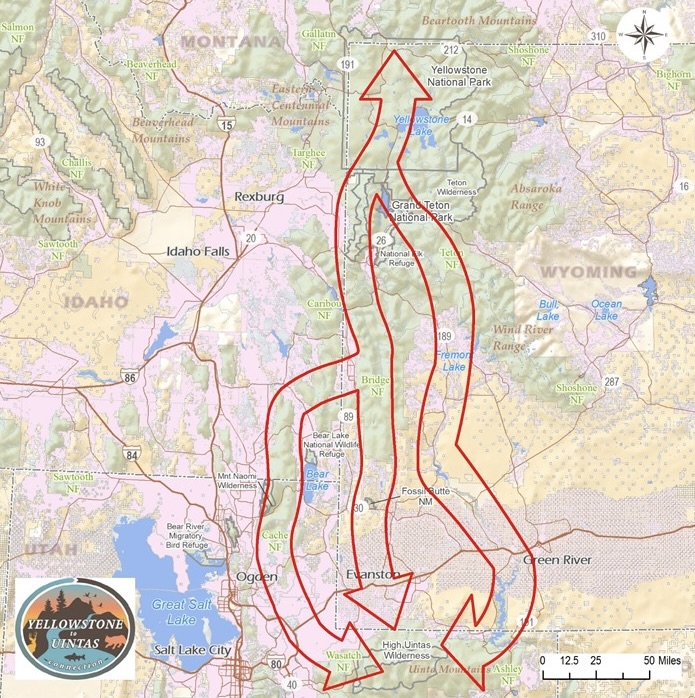

Part of the Western Wildway, the Yellowstone to Uintas Corridor links the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem south to the east-west Uinta Mountains in Utah. This link is essential for migratory movement since the arid, mostly flat Wyoming Basin in the central and southwestern part of Wyoming interrupts the flow of the Rockies. So the route south along Teton/Wyoming mountains in Wyoming and Bear River/Wasatch mountains in Idaho and Utah to connect with the Unitas around the Wyoming Basin provide the only mountainous link from the Northern Rockies to the Southern Rockies, affording a connection for mountain wildlife species.

While pronghorn, mule deer, and elk can make their way south through the Wyoming Basin with its lack of tree cover and sparse development, more cautious species such as black bear, gray wolf, badger, mountain lion depend more on the route through the high-elevation Uintas to reach the Southern Rockies, and of course the reverse if headed north. These mountain ranges not only provide for the continuation of the Rockies into Colorado, they offer connection to the Colorado Plateau to the south.

To advocate for protection and restoration for the Y2U Corridor, John Carter and Jason Christensen formed the Yellowstone to Uintas Connection in 2012. Carter, a PhD ecologist with a long interest in environmental preservation and restoration, fostered Christensen when he was a teenager. In the 1990s, the two began to purchase land along Paris Creek in Idaho’s Bear River Range while also exploring and assessing the wilderness of the Y2U. On extended hikes, Carter’s Akita, a large Japanese dog breed, accompanied them. “Keisha,” as he named the Akita, and her family carried much of their supplies during those treks.

Keisha’s memory endures in the name of the land the two have assembled, “Keisha’s Preserve,” which has grown to over 1,000 acres, including a second location in the Wyoming Range. Most of the land has been placed in a conservation easement to prevent any future development. Mule deer, elk, pronghorn, moose, greater sage grouse, Bonneville cutthroat trout, and beaver now find refuge on the preserve. Christensen and his wife Kandis manage the Paris Creek portion of the preserve, while Carter oversees the Wyoming portion that includes critical lynx and mule deer habitat within the Sublette Mule Deer Migration Corridor.

When the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, various accommodations were made to ensure bipartisan support for passage. While many accommodations were not desirable to wilderness advocates, they were necessary for Congressional passage of the Act. One of those, listed under “Special Provisions” under paragraph d(4) states “Within wilderness areas in national forests designated by this Act, … (2) the grazing of livestock, where established prior to the effective date of this Act, shall be permitted to continue subject to such reasonable regulations as are deemed necessary by the Secretary of Agriculture.”

In an egregious example of this accommodation, nearly 273,000 acres of the High Uintas Wilderness are being grazed by domestic sheep and cattle during the summer months. Thirty grazing allotments host as many as 10,000 cattle and 45,000 sheep. This summer grazing of thousands of domestic sheep in the High Uintas Wilderness has been a serious problem. Riparian areas and alpine basins have been overgrazed for decades. Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, that were eradicated from the Uintas early on by overhunting and diseases brought by domestic sheep, were reintroduced in the 1990s. The bighorns have struggled in competition with domestic sheep and only exist in numbers at the eastern end of the Uintas where domestic sheep do not graze.

Y2U’s Scientist John Carter has worked for decades documenting the environmental damage from livestock grazing in the High Uintas Wilderness and advocating for reductions. In response to a 2018 Forest Service announcement that it would review ten domestic sheep grazing allotments for permit renewal, Carter organized a coalition of environmental organizations to present concerns and recommendations on livestock grazing in the High Uintas, which harbor habitat for lynx, wolverine, and black bear in addition to bighorn sheep. Carter and his Wild Utah colleagues published an article in Journal of Geographic Information System, “Spatial Analysis of Livestock Grazing and Forest Service Management in the High Uintas Wilderness, Utah,” that detailed the environmental damage to the High Uintas:

“Previous monitoring has identified that large-scale erosion is occurring in the High Uintas Wilderness due to this practice of trailing and grazing domestic sheep in non-capable areas. … Forest Service management can address the problems in the High Uintas Wilderness by applying the analytical process we have provided and adjusting stocking rates and grazing periods based on the capable acres, current forage production and forage consumption rates, while applying a sustainable utilization rate.“

The Forest Service ultimately released the Final Environmental Impact Statement and draft Record of Decision in July 2025. To no one’s surprise, the decision is to continue grazing on the ten sheep allotments, which range in size from 12,000 acres to over 25,000 acres, for a total of around 160,400 acres. Of those acres, about 144,900 acres are inside the wilderness. Up to 10,300 ewe-lamb pairs and 3,000 dry ewes are authorized to graze the allotments each year.

Adding insult to injury, the government does little to charge for the privilege of taking forage off public lands. The grazing fee in 2025 on both BLM and Forest Service land is the same as past years, $1.35 per animal-unit-month, defined as “one cow and her calf, one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month.” This is a pittance when compared to the cost for grazing on private land, which on average is over $20/aum. Clearly this is a subsidy to the ranching industry. As author George Wuerthner says, “… you could not even feed a hamster for that amount of money for a month. So it’s a ridiculously low price, and it does not incorporate anywhere near the ecological damage that’s done by that livestock grazing, much less cover even the administrative fees and management costs that the public spends to manage these private businesses on our public land.”

The Green River corridor within the Wyoming Basin serves as the eastern-most of three north-south routes that make up the Yellowstone to Uintas Corridor network. The central migratory flow heads directly south from Yellowstone National Park through Grand Teton National Park and continues south along the Teton and Wyoming Ranges. The west branch of the migration route follows the Bear River Mountains in Idaho and then the Wasatch Range in Utah until all three corridors converge on the east-west Uinta Mountains.

Wanting to explore the Green River corridor, we travel into the Wyoming Basin on US 191 toward the Green and pass through the first of two overpasses for the Path of the Pronghorn. A large herd of these ungulates spends the summer season in and around Grand Teton National Park. Leaving Jackson Hole when snows accumulate, they follow the watershed of the Gros Ventre River, a tributary of the Snake, to penetrate mountains to the east, crossing 9,000-foot passes of the Gros Ventre Range, and descending into the Green River watershed.

Farther south, as they leave Bridger-Teton National Forest following available forage, the pronghorn cross private lands (some with conservation easements) as well as Bureau of Land Management and Wyoming State lands in the Green River Basin. Traveling 150 miles or more, they enter the northern reaches of the Red Desert in southeast Wyoming, one of the last remnants of high-desert ecosystems in North America, where they can access forage during the depths of winter. Come spring, the pronghorn return north along the same route, following emerging vegetation and returning to their summering grounds at Jackson Hole. This seasonal migration route has been passed down from one generation to the next as older animals lead the others along this pathway that archeological evidence suggests has been used for 6,000 years.

Crossing the Green River on its journey south, we pass through the overpass at Trappers Point and turn north. The paved road wanders through ranchland following the Green River upstream. After about forty miles, the road changes to dirt as it passes into Bridger-Teton National Forest and becomes Union Pass Road. The Green flows on the left, which we only glimpse briefly as I attempt to dodge potholes in the rough road, often unsuccessfully. “Washboard” was the warning used to describe the dirt track. Mule deer wander among the brush between the road and the river. After sixteen miles of jouncing, we finally arrive at Lower Green River Lake.

Walking down the glacial moraine to the lake shore, we stare across the water’s reflecting surface to Squaretop Mountain on the horizon. The road and river, after having traveled north, both execute a U-turn to the lake so that we’re now looking southeast to the imposing monolith rising 3,700 feet above surrounding terrain in the Bridger Wilderness within the national forest. Between this lower lake and the mountain, Upper Green River Lake lies out of sight. While these two lakes are referred to as the source of the river, the actual source lies many miles farther in the mountainous Wind River Range where melting glaciers and rainfall descend to form the streams that feed the lakes.

The wildlife corridor that includes the movement of pronghorn and as well as mule deer from Jackson Hole and Hoback Basin through the Upper Green River Basin continues south through Wyoming, generally following the Green River corridor through an arid region of grass and shrub. South from the Wind River Range, the Green River encounters the 8,000-acre reservoir behind Fontenelle Dam, an earth-fill structure erected in the 1960s initially for irrigation and power generation. As a participating project of the Colorado River Storage Project for the upper Colorado River Basin, it now serves as water storage. Southeast of Fontenelle Dam, the Green runs through the Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge, a haven for migrating birds along 36 miles of the river. The name originates in the Shoshone name for the Green—Seeds-ké-dee-agie, meaning “river of the prairie hen,” a reference to the greater sage grouse that inhabit this riparian corridor and the surrounding sageland of the Green River Basin.

The town of Green River, Wyoming, at the time a village on the Union Pacific Railroad, served as the starting point for John Wesley Powell’s explorations of the Colorado River Basin. Starting on the Green River on May 24, 1869, he says, “The good people of Green River City turn out to see us start. We raise our little flag, push the boats from shore, and the swift current carries us down.” Walking from that first day’s camp, he says,

“Barren desolation is stretched before me; and yet there is a beauty in the scene. The fantastic carvings, imitating architectural forms and suggesting rude but weird statuary, with the bright and varied colors of the rocks, conspire to make a scene such as the dweller in verdure-clad hills can scarcely appreciate. … Away to the south the Uinta Mountains stretch in a long line,—high peaks thrust into the sky …“

Two days later, Powell and his nine-man crew in four boats approached the east-west range of the Uintas.

“The river is running to the south; the mountains have an easterly and westerly trend directly athwart its course, yet it glides on in a quiet way as if it thought a mountain range no formidable obstruction. It enters the range by a flaring, brilliant red gorge, that may be seen from the north a score of miles away. The great mass of the mountain ridge through which the gorge is cut is composed of bright vermillion rocks … This is the head of the first of the canyons we are about to explore—an introductory one to a series made by the river through this range. We name it Flaming Gorge.”

From Red Canyon Overlook, we look down to the Flaming Gorge Reservoir that stretches into the distant recesses of the canyon, backed up by Flaming Gorge Dam. While the national forest around the gorge still hosts a multitude of wildlife species, including mule deer, elk, bobcat, black bear, and bighorn sheep, some of the apex predators Powell noted are mostly gone—grizzly bears, wolverines, mountain lions, wolves. Habitat in the bottom of the gorge has been lost. Don Hatch, river guide with Hatch Expeditions who knew the gorge before the dam, is quoted in A Green River Reader, “… the living space was the bottom of the canyon … the wildlife was along the bottom. So when you put in the dam there and flooded it, it essentially killed all the living space for the animals.”

At Red Canyon, the river has turned east after flowing south through Flaming Gorge into the Unita Mountains. As the Green attempts to sidestep the range, the river virtually outlines the eastern reach of the Uintas. As Powell describes it,

“The canyon is cut nearly halfway through the range, then turns to the east and is cut along the central line, or axis, gradually crossing to the south. Keeping this direction for more than 50 miles, it then turns abruptly to a southwest course, and goes diagonally through the southern slope of the range.”

The river sweeps east into Colorado where a miles-long stretch of the Green River in Browns Park has been set aside as another national wildlife refuge for migratory and resident birds. To the south lies Dinosaur National Monument, 210,000 acres straddling the Colorado-Utah state line. Obviously known for its fossils of prehistoric creatures, the monument just as importantly protects a long, scenic stretch of the Green River.

Emerging from the national monument on the Utah side, the Green leaves the Uinta Range, which serves as the geologic boundary between the cold, wind-swept plains of the Wyoming Basin on the north and the hot, arid Colorado Plateau on the south. The river flows southwest into the open Uinta Basin bordered on the west by the Wasatch Range and on the south by the Tavaputs Plateau, part of the Colorado Plateaus Province. Streams flowing from the southern slope of the Uintas into the basin, including the Uinta River, gather in the Duchesne River, which flows east to the Green.

As the Green River continues south, it cuts through the Tavaputs Plateau, dividing the West Tavaputs Plateau from the East Tavaputs Plateau. Accompanying J.W. Powell on his 1871 expedition, seventeen-year-old Frederick Dellenbaugh, who was the official artist on the expedition, noted that a small party

“… in the morning, August 11th, climbed out to study the contiguous region which was found to be not a mountain range but a bleak and desolate plateau though which we were cutting along Green River toward a still higher portion. This was afterwards named the Tavaputs Plateau, East and West divisions, the river being the line of separation.”

Powell and his crew called this cleft in the plateau “Desolation Canyon.”

“After dinner we pass through a region of the wildest desolation. The canyon is very tortuous, the river very rapid, and many lateral canyons enter on either side. … The walls are almost without vegetation; a few dwarf bushes are seen here and there clinging to the rocks, and cedars grow from the crevices … ugly clumps, like warclubs beset with spines. We are minded to call this the Canyon of Desolation.”

When they emerged from Desolation Canyon, they had about a mile of country more open before entering “another canyon cut through gray sandstone,” which they called “Gray Canyon.”

Farther to the south, the Green River flows across the arid high-elevation plain. “The course of the river is tortuous, and it nearly doubles upon itself many times,” Powell says. “The water is quiet, and constant rowing is necessary to make much headway.” Still, the river becomes even more “tortuous” as it enters another canyon.

“About six miles below noon camp we go around a great bend to the right, five miles in length, and come back to a point within a quarter of a mile of where we started. Then we sweep around another great bend to the left, making a circuit of nine miles, and come back to a point within 600 yards of the beginning of the bend. In the two circuits we describe almost the figure 8. The men call it a ‘bowknot’ of river; and so we name it Bowknot Bend (and) …we name this Labyrinth Canyon.”

Labyrinth lies at the doorstep of Canyonlands National Park. Within the park, the Green River reaches a confluence with the Colorado River.

Although the Green River flows through a mix of federal, state, and private land, on many a wish list would be a single protected corridor to tie all these river miles and canyons together. Author Fred Swanson says,

“The river forms a single green thread connecting these disparate settings and jurisdictions, flowing almost entirely through public lands, from its headwaters in the northern Wind River Range of Wyoming to its confluence with the Colorado River deep in Canyonlands.”

The approximate 200 miles of river from Dinosaur National Monument to Canyonlands National Park would be a good start on establishing a preserved Green River corridor.

© Russ Manning. All Rights Reserved.

A pdf of much longer text and complete references for Yellowstone to Uintas: Path of the Pronghorn may be downloaded at the link below.